Planning had gone on for years. Israel would use advanced aircraft but forgo precision munitions in favor of a desire to totally destroy the target. Israeli F-16s were to fly to Iraq and, in just 90 seconds, eviscerate a nuclear reactor that could one day threaten Israel and the region. If it worked, it could prevent Saddam Hussein’s Iraq from developing nuclear weapons and holding the region hostage.

If it failed, Israel knew that Saddam might emerge stronger and that Israel, already isolated on the world’s stage, could be more isolated and Iraq might have a reason to strike back.

It was a different time. Israel was threatened from Lebanon by Palestinian terror groups armed with rockets. Most of the region was against the Jewish state, including a powerful and economically successful Iraq. Iran, after the Islamic Revolution, was also emerging as a major opponent of Israel. There were stirrings of protest in the West Bank. Israel had signed a peace treaty with Egypt, a momentous occasion, and it was withdrawing forces from Sinai. The UN Resolution declaring “Zionism is racism” had been passed in 1975 and was still on the books. It would not be repealed until 1991.

In 1980 the Middle East was dominated by a series of powerful non-democratic regimes. These included Saddam Hussein in Iraq, who had come to power and promised rapid industrialization of the country. Iraq was one of the key powers in the region at the time with an army that expanded to almost one million men under arms by the 1990s. It was the fourth-largest army in the world. Iraq would eventually acquire around 5,700 tanks – including advanced T-72 models – and thousands of artillery pieces. It purchased arms from countries around the world, including China, the Soviet Union, Italy, Czechoslovakia and others, importing some $24 billion in military equipment. Iraq’s amassing of this power had a profound effect on the region.

Iraq pursued weapons of mass destruction, leading to the Israeli raid on its Osirak reactor in 1981. It had acquired chemical weapons, which it used in the Iran-Iraq war. It also worked with terrorists, such as the terror leader known as Abu Nidal. Iraq’s leading role in the conflict with Iran led it to become increasingly tied to Kuwait and the Gulf states, serving as a buffer between the Arab states and the Islamic revolution of Iran that had broken out in 1979.

This was important because the Iran-Iraq war appeared to absorb much of the militancy of the 1980s. The result would be an empowered Iraq that would launch an invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

TODAY THE raid on Osirak is seen through the prism of what came after.

The successful airstrike involved 14 F-15 and F-16 fighter jets dropping a dozen munitions on the reactor. One French technician was killed. In only several minutes on that day, Israel established a doctrine that it would act to prevent any existential threat involving weapons of mass destruction in the region. Prime minister Menachem Begin said that Israel would not allow nuclear weapons in the region to threaten Israel. The shadow that was cast is important because years later the controversy over Iran’s nuclear program continues to be framed according to the rules of June 7, 1981.

Not everyone was happy with this doctrine. The international community, since Israel’s creation, has largely worked to excuse the endless wars against the Jewish state. In the 1950s the establishment of Palestinian refugee camps was intended not just as a measure to help displaced people, but to create an endless UN-supported program specifically for those refugees to keep them hungry for a “right of return” to Israel.

The Western powers and Soviet bloc worked with fanatical Arab nationalist regimes in the 1960s – not to get them to stop their warmongering against Israel, but to enable their hostile views. Weapons were sold to Egypt, Syria and other states hostile to Israel, enabling them to vastly expand their armies, and scientists came to aid them in their missile programs. Like Iran today, these countries chose to use hatred of Israel as an excuse to build up massive military-industrial complexes devoted to the destruction of the Jewish state. Instead of holding them back, Western countries caved to their excuses about how they had to fight Israel and that the “conflict” was the central issue in the region.

International terrorism, directed in an unprecedented way against Israel, led to atrocities such as the Munich Olympics massacre, all ignored or excused by many Western governments while the terrorists themselves received backing from Soviet bloc countries and succor from regimes like Saddam’s Iraq.

Even in 1993 when the full evils of the Saddam regime were already clear, after he had perpetrated genocidal attacks against the Kurds in the 1980s using poison gas and invaded Kuwait in 1990, there were still experts arguing against Israel’s actions. An article in the International Journal of World Peace in 1993, Donald Boudreau argued against the “conventional wisdom that the act [by Israel] made a positive contribution to Israeli and international peace and security… the author laments the establishment of several ominous precedents.”

Of course, there is no companion article lamenting the precedent of Saddam Hussein using poison gas to attempt genocide of the Kurds in Iraq. For some reason that was not a problem for international peace, yet Israel bombing Saddam’s reactor was. The Osirak raid illustrates that no matter what Israel does, it is always the “problem.” Saddam invading Iran at the opening salvo of the Iran-Iraq war, a war that dragged on for almost a decade killing masses of people, was not a bad precedent. Israel carrying out a precision strike on a nuclear reactor? Very controversial. For the same reason Israel’s precision response last month to Hamas rocket fire led to an international anti-Israel outcry.

The naysayers have one view of Osirak. They didn’t want Israel defending itself and likely preferred Saddam’s Iraq to acquire nuclear weapons, much as today the quiet lobby behind Iran’s desire for nuclear weapons pretends it is merely supporting peace when in fact it is paving the way for Iran to develop a nuclear weapon and hold the region hostage – as it already holds the region hostage with drones and missiles.

WHAT WAS achieved on that unprecedented day, June 7, 1981? According to a 2004 thesis by Peter Ford at the Naval Postgraduate School in California, the preventive strike was “valuable primarily for two purposes: buying time and gaining international attention. Second, the strike provided a one-time benefit for Israel. Subsequent strikes will be less effective due to dispersed/hardened nuclear targets and limited intelligence.”

Iraq was able to obtain a reactor through its close relations with France. It was still technically at war with Israel: Iraqis had been sent to the frontlines in the Golan to fight Israel in 1973. Iraq was showing its brutality by executing Jews as well. As usual, the international community worked with Iraq instead of condemning the executions, warmongering and brutality.

Saddam’s Ba’athist regime, like Iran’s today, was sophisticated. It had high-quality educated people at its top ranks. It was also a modernizing country with new planned cities, and the rural countryside was being remade by Stalinist-style planning. Iraq was, in some ways, the envy of the Arab world with its healthcare and education systems ranking well in the region at the time. Brutal, yes, but also relatively successful.

Hussein approached the French to acquire a gas-graphite reactor for uranium to be enriched to 93%.

“Possessing an Osiris-type reactor offered two primary benefits to Hussein: its plutogenic traits offered him a potential source of weapons-grade nuclear material and the fuel used to run Osiris also was weapons-grade material,” writes Ford. Saddam openly said that the agreement with France would lead to the first “Arab atomic bomb.”

Iraq sought out a 70-megawatt Osiris-style reactor and another training reactor. It also sought a plant from Italy to separate plutonium. The training reactor, dubbed Tammuz II, began operations in February 1980. Enriched uranium arrived in Iraq. The window to stop the process was closing. Reactor cores, damaged via sabotage in France, would arrive. Once the reactors were operational, a strike could cause radioactive material to spread all over Iraq. The reactor complex on the banks of the Tigris River was a large square facility, with the main Tammuz Osirak reactor having a white concrete dome.

Ironically, it was the Iranians, using F-4s, who first tried to destroy the reactor. They were on the frontline against Saddam’s brutal army; Israel was still far away. But the Iraqis made clear that it was Israel the nukes would be used against. Israel countered the threat through the media and via attempts to derail or slow down the pace of Iraq’s nuclear program.

“Israel exerted seven years of diplomatic pressure on nations around the world in the attempt to prevent Iraq from getting the Osirak reactor,” Ford writes.

Critics of Israel often say the country does not do enough diplomacy to achieve peace. The Iraqi reactor story illustrates how even when Israel does everything possible to beg the international community to listen and do something, no help is forthcoming. This is largely because Western powers pay lip service to things like “non-proliferation” but actually do little to prevent it.

THE STRIKE did not occur in a vacuum. Israel had to weigh international reactions and domestic political repercussions. It is thought that ordering the strike benefited those in charge, the positive risks outweighing the potential negatives.

Once the decision had been made, Israel had to also make sure that the tools it would use were sufficient. When Israel first looked at how to stop the Iraqi threat it only had F-4 Phantoms and A-4 Skyhawks, not long-range planes capable of the mission. That changed with the Iranian Revolution. F-16s destined for Iran as part of “Peace Zebra” were rerouted to Israel as part of an acquisition called Peace Marble, covering 75 planes. The planes came in 1980. The super-modern F-16, just off the production line, was ideal for the mission.

With modern F-16 and F-15s Israel had the warplanes and munitions to accomplish the task.

“Both [warplane types] had advanced Inertial Navigation Systems allowing them to fly long distances without the need for ground-based navigation aids. The IAF had the right tools to accomplish the mission,” notes Ford.

The decision of what weapons to use mattered as well. Israel opted for a more dangerous raid using non-precision weapons rather than those that might give a “stand-off” capability where the planes could drop their smart bombs and then be sufficiently safe from anti-aircraft fire. A total of 16 MK84 2,000-pound bombs would be dropped into the reactor with delayed fuses, designed for maximum destruction.

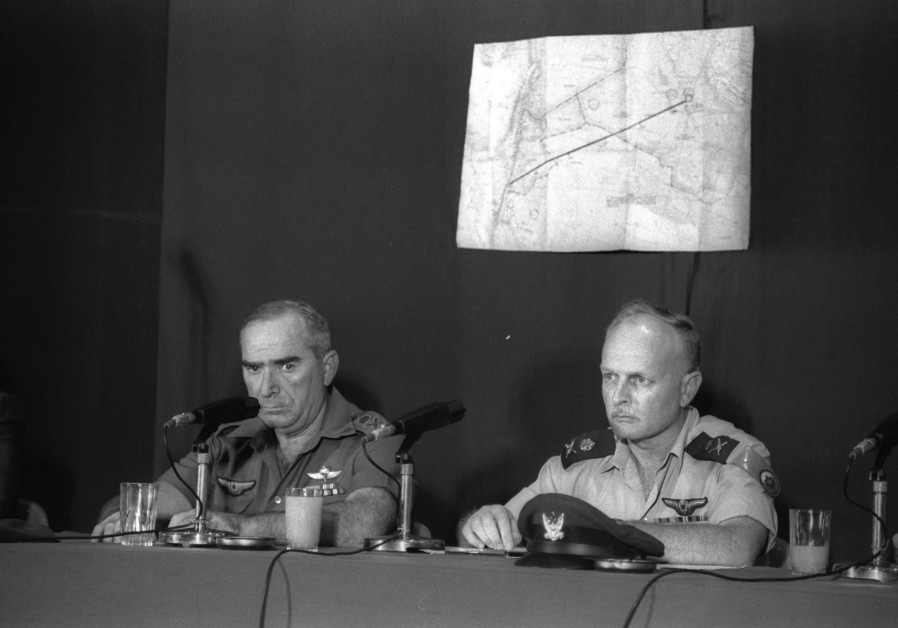

The pilots, along with Israel Air Force Maj.-Gen. David Ivri and IDF chief of staff Rafael “Raful” Eitan, clustered at Etzion Air Base prior to the strike, dubbed Operation Babylon (also known as Operation Opera). It was the eve of Shavuot. The pilots were briefed. The six F-15s and eight F-16s flew the complex mission over Saudi Arabia, entering Iraq from the miles of open desert that form the boundary between Iraq and Saudi Arabia. They had to fly low, some 100-150 feet from the desert landscape. While the F-15s used radar and electronic counter-measures, the F-16s continued their bomb run to the reactor southwest of Baghdad.

There were other obstacles as well. Jordan’s King Hussein, according to reports, saw the F-16s pass over and a warning was sent to Iraq according to a 2012 Air Force Magazine report. It was just after 4 p.m. and the reactor was to be struck at sunset. Radio silence had to be maintained and the pilots had to avoid Saudi early warning systems operating to the south. There was a larger context here. At the time, controversy had grown in the US over sales of F-15 enhancements to Saudi Arabia and AWACS radar planes. Such advanced aircraft were not in the hands of Riyadh yet.

The mission’s success not only gave Israeli additional military respect around the world, it also aided deterrence. It once again proved its capabilities for using the latest aircraft. Ford notes that “the IAF used the F-15, designed for long-range detection and air superiority, in its optimal role: protecting strikers as they dropped their munitions. Similarly, the IAF used the F-16 in its optimal role as a strike fighter against heavily defended targets. Israel was the only nation in the region that possessed these aircraft and tactical knowledge about their optimal use.”

Today Israel is pioneering uses for the F-35, having received two dozen of the aircraft in two squadrons, with the plan to acquire up to 75 of the planes.

The raid on Osirak was a watershed moment. It changed the region and ushered in a new era of Israeli dominance. Where once Israel’s military abilities were contested by conventional militaries like Egypt and Syria, by the 1980s and 1990s Israel would possess the strongest most capable military in the region.

But that hasn’t changed the equation when it comes to non-conventional weapons, such as nuclear weapons or Iran’s missiles and drones, the kind Hamas has used recently. Israel’s use of advanced warplanes, such as the F-15 and F-16 and now F-35, isn’t a magic wand to win wars.

Dangerous facilities, such as Syria’s nuclear reactor that was destroyed in 2007, can be stopped – but more threats will emerge.